Cyberjealous

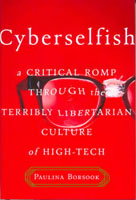

Cyberselfish: A Critical Romp Through the Terribly

Libertarian Culture of High-Tech

by Paulina Borsook

PublicAffairs, 2000. 267 pgs.

Reviewed by Bob Murphy

[Posted July 21, 2000]

Every generation has its defining moment, when the

Manichaean unfolding of history lets the good guys gain the

upper hand. These moments may be tumultuous political

upheavals, such as the New Deal or civil rights protests.

But they also consist in the publication of literary

treasures, such as Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin or

Sinclair's The Jungle. Cyberselfish, the

latest masterpiece by Paulina Borsook, will one day surely

be placed in this latter category.

Every generation has its defining moment, when the

Manichaean unfolding of history lets the good guys gain the

upper hand. These moments may be tumultuous political

upheavals, such as the New Deal or civil rights protests.

But they also consist in the publication of literary

treasures, such as Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin or

Sinclair's The Jungle. Cyberselfish, the

latest masterpiece by Paulina Borsook, will one day surely

be placed in this latter category.

True to her concern for "the vulnerable, the ones

who weren't able to cash out, those whose skillset or native

endowment doesn't fit well into the shiny happy new

information economy" (37), Borsook's work entertains

without even being opened--as the marketing hustlers

like to say, "no purchase necessary."

Indeed, the man of modest means may derive a pick-me-up

simply by picking up Borsook's book. The front cover

features a stunning red backdrop--which can only be an

allusion to Poe--and the mesmerizing image of a hideous pair

of glasses (complete with Scotch tape on the frame), which

breaks all the rules by not even being centered in

the picture.

To speculate on the meaning of this is perhaps as

foolhardy and blasphemous as proffering explanations of

Marx' law of surplus value, but in any case the present

reviewer feels the off-center placement is symbolic of how

'skewed to the right' such "technolibertarians"

appear to the rest of us.

But when one turns to the back cover, well! Here

Borsook smuggles an attack that would astound a Trojan. The

benighted boob, fresh from his oh-so-difficult job shuffling

papers in the office, will no doubt take the critics' praise

(as if Borsook needed promotion) at face value.

This Anglo-Saxon balding male--anxious to get home, crack

a Bud Light, and watch John Rocker pointlessly throw a

little white ball really really fast, only to have it tossed

back to him so he can do it again--will read that Borsook is

"agreeably caustic," "eloquent but vaguely

irritated," "[s]cathing but not incorrect."

He will swallow whole the claim that Borsook "oozes

style and an authoritative voice that lets you know she's

probably read more books than you."

The very idea that Borsook would consent to such

crass corporate cookie cutter compliments, to such an

irrelevant understatement as the last quote--akin to

presenting an atheist with a Testament and the admonition,

"He's probably seen more lepers than you"--is

frankly insulting. Such shameless salesmanship--which has

given us commercialized Olympics and the choreographed

spontaneity of Woodstock '99--is clearly a satire, plucked

from Borsook's prodigious arsenal of literary devices.

Borsook is just having fun with the reader, and has

obviously ghostwritten these 'reviews.' The chosen few of us

who get it, who recognize her subtle ploy, feel a

rush of righteousness that this reviewer has not experienced

since he first chained himself to an old-growth redwood.

Whatever we may long for, the sad fact is, we still live

in a world dominated by cost-conscious capitalists, and this

reviewer's employers are no exception. As such, he cannot do

Cyberselfish the justice it deserves, and regrettably

must restrict his attention to the two sections of the work

where he feels most competent.

(Incidentally, the present writer was initially inclined

to suggest this latter approach to Borsook, but then

realized upon further reflection that such a superlatively

cosmopolitan lady as our author needs no lecture from him

on the virtues of experimentation.)

Borsook's first target is Bionomics, the spawn of

apologist Michael Rothschild:

Bionomics [describes] the way the world works in terms of

learning, adaptation, intelligence, selection, and

ecological niches. It favors decentralization and trial

and error and local control and simple rules and letting

things be. Bionomics pays homage to Friedrich Hayek, one

of the residents in the traditional libertarian pantheon,

who believed that only free markets can lead to freedom

(been to China lately?) and that command and control (all

government interventions of course irresistibly leading to

Stalinesque collectivization of farms) leads to serfdom.

(32)

Borsook's brilliant analysis stands on its own and so no

comments will be offered and so we move on:

Bionomics states that "the economy is a rain

forest." The Bionomics argument goes that a rain

forest ecosystem is far more complicated than any machine

that could be designed--the idea being that machines, and

machine-age thinking, are the markers of Bad Old Economic

thinking. No one can manage or engineer a rain forest, and

rain forests are happiest when they are left alone to

evolve, which will then benefit all the happy monkeys,

pretty butterflies, and funny tapirs that live in them. In

our capitalist rain forest, organizations and industries

are the species and organisms. Although if a corporation

is the analog for, say, an individual tapir, then what is

the rain forest analog for an individual person? A

mitochondria?

What about the fact that actual rain forests are now

being destroyed because of the free market? (32)

Although it borders on sacrilege to deconstruct Borsook's

prose, it is the responsibility of the present reviewer to

point out all that has been packed into this brief snippet.

The capitalization in "Bad Old Economic thinking"

is an ingenious attack on the deploring tendency of the

technolibertarians to eschew serious debate and instead

construct simplistic straw men.

Borsook's references to tapirs and mitochondria showcase

the incredible breadth of her knowledge--indeed, she has

read many books. Our author first explodes the Bionomic rain

forest analogy with a neat reductio ad absurdum.

(Which prompts the tantalizing question, What is the rain

forest analog for Cyberselfish? This Borsook does not

specify, but given her concern for the environment, it would

no doubt be biodegradable and make excellent fertilizer.)

After this stunning jab, Borsook finishes off her Bionomic

opponent by placing the final sentence quoted above as a

paragraph unto itself.

The tender reader may feel that Borsook's scathing

attack, though not incorrect, is a bit too merciless.

But this is not at all the case. For these self-styled

freedom lovers--where "freedom" is used in an

incredibly Victorian sense, of course--are not blissfully

ignorant of the utter absurdity of their position. When the

plight of the Amazon rain forests is pointed out to them,

they bravely maintain that South American countries are not

examples of what they 'mean' by "free markets" (as

if issues of social justice revolved around semantics!).

That Borsook has neglected to even bring up this silly

rebuttal is an example of her under-appreciated compassion.

Unfortunately, Bionomics is not the only refuge of

today's incipient fascists. A more virulent strain of

egoists has arisen:

"Anarcho-capitalist," which is how many

cypherpunks describe themselves, is as hardheaded as it

gets. This dimly veiled social

Darwinist/property-is-next-to-godliness/everything-is-contractual

political and economic philosophy (with Nietzsche crawling

around somewhere inside there, too) was first articulated

by economics professor Ludwig von Mises in the 1920s and

1930s, echoed later by economist and Mises student, Ayn

Rand-follower Murray Rothbard-and portrayed in sci-fi

writer Robert A. Heinlein's The Moon is a Harsh

Mistress, which posited a utopian society based on

libertarian, Nietzschean ideals. (97-98)

This reviewer must confess that he finds the sheer wit of

this passage to be simply impenetrable. Based on his meager

studies, he had never made the connection between

libertarianism and Nietzsche. He was rather sure that the

reactionary Ludwig von Mises had ridiculed anarchists as

hopelessly na´ve, and that the exasperating Murray Rothbard

had referred to the products of the information superhighway

as "mindless pap."

Alas, sometimes our author's sarcasm--though always a

delight--makes it difficult to distinguish historical

revisionism from hilarious hoaxes. He will of course

diligently watch C-Span's "Book Notes," and

perhaps ask Borsook herself at the next AIDS rally, but in

matters such as these, she usually adopts the stance of the

magician with regard to his tricks. No doubt these apparent

antinomies will occupy economists and philosophers no less

than biblical scholars attend to the exact circumstances of

the death of Judas.

This cruelly meritocratic world-to-come described in

cypherpunk postings is reminiscent of 1950s science

fiction. In these yesterday's tomorrows, the males with

superior intellect, as measured in rocket-scientist terms,

ruled. (In current terms, benefiting hugely from cash

sucked from high tech entrepreneurial activities,

generating untraceable untaxable financial reserves and

tweaking the global monetary supply through anonymous

transactions.) And incidentally, in these Good Societies

of the future, the ruling males also scored with the

initially reluctant biology-officer bodacious babes.

Aldous Huxley, writing years before, commented obliquely

on a society of the future based on Nietzschean ideals in

Brave New World (the genetically determined top-drawer

alpha males were explicitly assigned foxy females)-but

Huxley wrote his book as a cautionary satire. In the same

way that the more you run away from something, the closer

it gets to you, Huxley's teaching story about a land of

ultimate government control doesn't look so different from

the cypherpunk social-Darwinist promised land of total

libertarian freedom. (98)

After reading this passage, one is immediately struck by

the usage of the always amusing

it-doesn't-take-a-rocket-scientist genre. The admirable

alliteration serves to foreshadow Borsook's seamless

transition to a compassionate commentary on the sexual mores

of the technolibertarian:

[I]t's anomalous that many many cypherpunks are not

married, have never been married, and have no kids..

Katherine Mieskowski.called the people who manifest [the]

convergence of computer nerd and weird sex "nerverts."

When I read her column I knew exactly what she meant, for

I have run into nerverts many times. Mieskowski got a

nervert practitioner to explain this connection between

whacked-out sex and nerditude.. This is not to say that

all nerds lack social or courting skills..But a strong

intersection exists between nerds and fringe sex, just as

a strong intersection exists between nerds and neopagans.

(99, 101)

The emphatic empathy of this passage is typical of

Borsook's work. She is a spoofing and witty and clever and

sarcastic and creative and energetic writer, who no doubt

spent her entire adolescence brimming with anticipation for

the day when our sick culture would finally appreciate these

traits. (A glance at the author's stunning picture on the

book jacket confirms this conjecture.)

We treat the reader to one final gem:

As the SDS (Students for a Democratic Society) of the

technology community-more outrageous than most,

articulating the funnest, extremest, most

tear-down-the-walls/two-four-six-eight,

organize-to-smash-the-state notions of how the world

should work, will work, once their anti-good-boy vision

comes to pass-cypherpunks express and inform the ethos of

the rest of the technolibertarian community. And the

original cypherpunk manifestos and newsgroup

postings...coalesced a political way of being, a coherent

adversarial pose for being a hardheaded geek. (97)

Here we have Borsook at her finest, exhibiting an

effortless marriage of poetry and political commentary not

seen since Bob Dylan's "Hurricane."

Believe it or not, there's more where that came from.

Borsook never lets up, filling all 267 pages of Cyberselfish

with her uncanny wisecracks and wisdom. The work will serve

as an excellent introduction to the new reader, although one

cannot help but blush when making such a presumptuous

recommendation. (Which of the Bard's plays 'ought' to be

read first?) And the devoted fan, who has grown up on a

steady diet of Borsook's contributions to Wired, Newsweek,

and Salon, will have only one thing to say after

reading this book: She's still got it!

--------------

Bob Murphy is a summer fellow at the Mises Institute.

Send him MAIL.

518 W. Magnolia Avenue

Auburn, Alabama 36832-4528

(334) 321-2100 -- Phone

(334) 321-2119 -- Fax

mail@mises.org

|